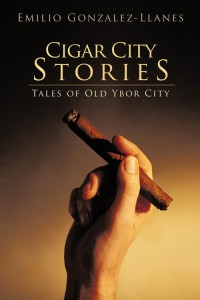

Friday night I fixed an early dinner for Luisa, Marley and me and then headed to the village of Occidental to attend the launch of Cigar City Stories: Tales of Old Ybor City by Emilio Gonzalez-Llanes at the Occidental Center for the Arts (OCA).

I didn’t have a clue what to expect. I’d never heard of anything called Cigar City or Ybor City but I do enjoy hearing, and supporting, other local authors. I’ve attended several book launches at OCA. Our long-time friend, Gretchen Butler, launched her wonderful book, Wild Plum Cafe at OCA and, more recently, a terrific book, The Body’s Perfect: A novel in Stories by Christopher Reibli, was released there. Gretchen had a local folk/roots group play before her reading. Christopher has his own band and they played before the reading. Christopher also sings.

I didn’t have a clue what to expect. I’d never heard of anything called Cigar City or Ybor City but I do enjoy hearing, and supporting, other local authors. I’ve attended several book launches at OCA. Our long-time friend, Gretchen Butler, launched her wonderful book, Wild Plum Cafe at OCA and, more recently, a terrific book, The Body’s Perfect: A novel in Stories by Christopher Reibli, was released there. Gretchen had a local folk/roots group play before her reading. Christopher has his own band and they played before the reading. Christopher also sings.

When, to a packed audience, the program started on Friday, Cuban music played on a CD and Emilio, a fit guy in his mid 70’s, came dancing out on stage. He danced on stage for 2 or 3 minutes. Are you getting the picture here? I don’t have a band. I don’t dance solo (at least in public) but I’m scheduled to be the next book launch (April 19th in case you can make it!). With every shake of his maracas, my heart sank.

I’m reading from my memoir: Sometimes I See You. I don’t think it’s depressing, but it is about our family during the 24-years that my daughter, Shoshana, was alive. Maracas won’t cut it.

Forget that. I really enjoyed Emilio’s reading. The stories vibrate with detail and emotion and expose a world I’d never known. And, when I got home, I realized that I had more in common with Emilio than I’d first thought. My maternal grandfather, who emigrated from Minsk to New York at the end of the 19th century, made cigars in the Bronx, much as immigrants from Cuba made cigars in Ybor City.

And, even better, Judith Moorman who is organizing my “launch” assured me that I wouldn’t need to dance!

But, if I did . . . ?